A Look Inside the American Sign Museum

Bright lights, blinking neon, and signs from the past all in one glowing place.

Last week, I had the opportunity to visit Cincinnati, Ohio, to spend a day and a half exploring every corner of the American Sign Museum, and to say I was in heaven is an understatement.

A friendly reminder that The Anvil is a free publication by yours truly, Jenna, a Los Angeles-based sign painter. If you’d like to support me further, consider signing up for a paid membership. Sharing articles with friends and to social media really helps, too. Thank you!

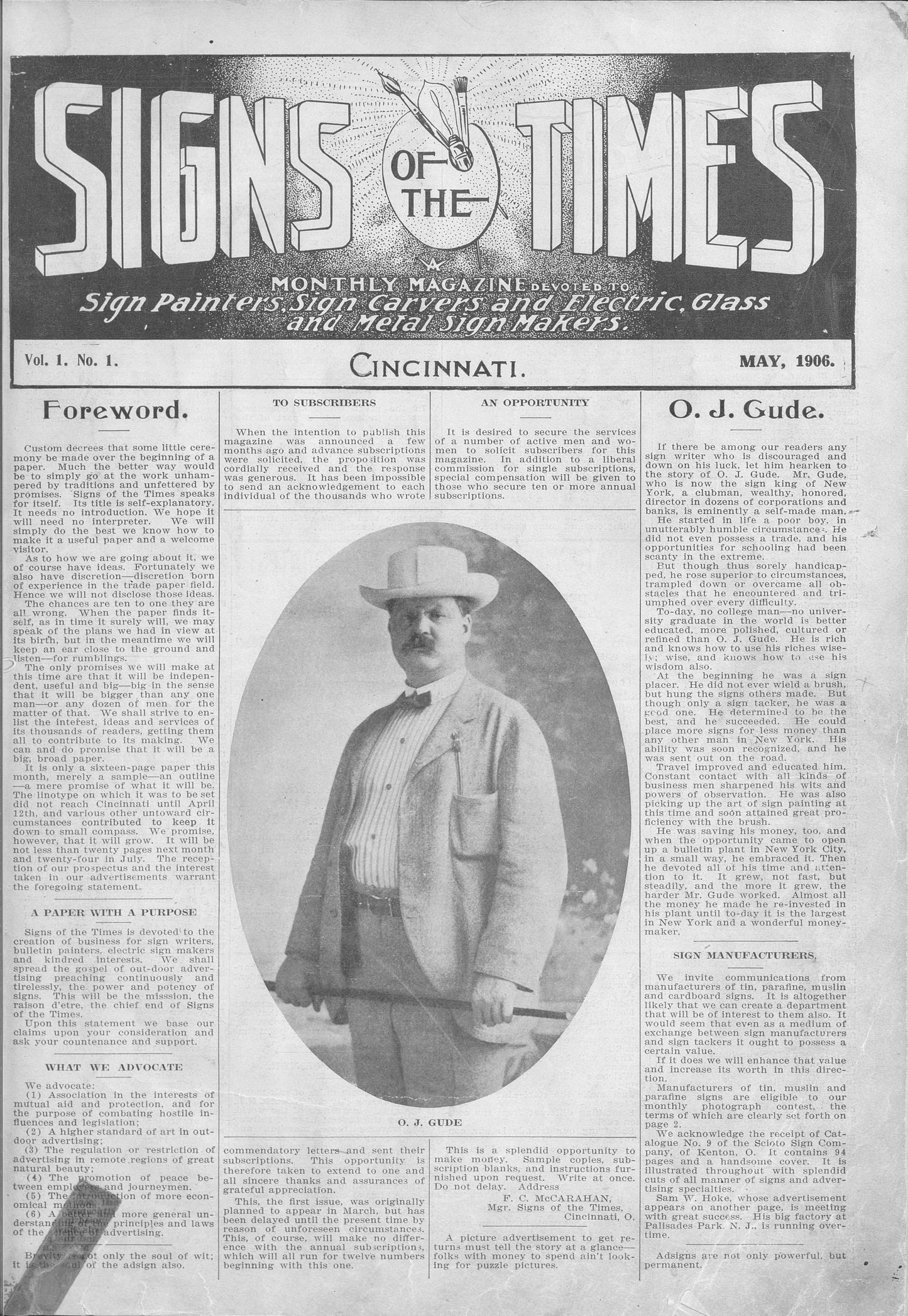

The museum was founded in 1999 by current founder and curator Tod Swormstedt (who absolutely rules, by the way), but its history goes back to the Cincinnati-based Signs of the Times magazine, a now-digital and print publication that focuses on the sign industry as a whole. It was first published in May 1906 as a “monthly magazine devoted to sign painters, sign carvers and electric, glass, and metal sign makers.” (Side note: The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County have digitized nearly 197issues of the magazine in the archive here.)

The magazine was founded by Colonel William H. Donaldson, and throughout the years leadership eventually was passed to the Swormstedt family. A fourth-generation Swormstedt editor, Tod spent 26 years on the staff of Signs of the Times before founding the museum in 1999, then as the National Signs of the Time Museum; it was later renamed and re-opened as the American Sign Museum in 2005.

As the collection grew—both in quantity and in size of massive neon acquisitions—the museum moved to its current home in Cincinnati's Camp Washington area, into the 1918 Oesterlein Machine Company-Fashion Frocks, Inc. complex. The complex first manufactured tools, followed by women’s clothing in the 1930s, and even made parachutes during World War II.

Winding through the museum, you are taken on a journey through sign painting history, exploring early wood-carved, porcelain, glass, and metal letters; wire mesh sign; painted wood and metal signs; enamel signs, lightbulb signs; and neon signs.

Most of the letters and signs pictured below are from the early 1900s. The wire mesh Longley’s sign dates back to 1900-1910, and the gilded letters are from around 1900-1930.

The examples below are of early painted and trade signs, dating mostly to the 1930s and 1940s—the 1935 Kant-Rust sign at the top was actually screen-printed on tin and framed with wood.

The museum also has a set of the roadside Burma-Shave signs, which were spaced out for drivers to read the message as they drove:

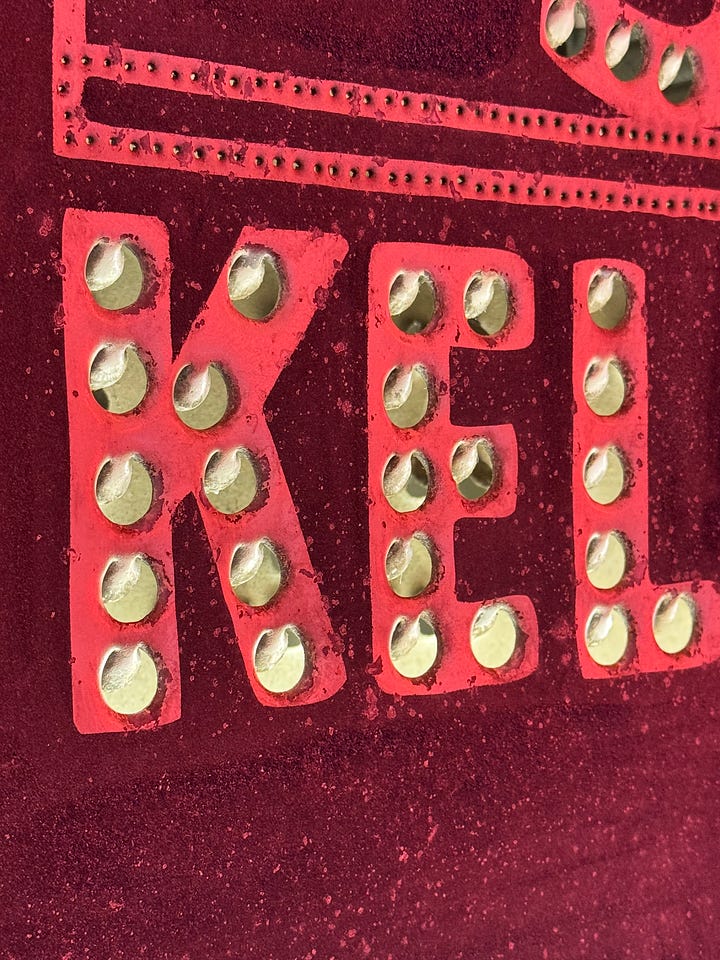

Lightbulb signs were popular from 1900 through 1925 and served as the predecessor to neon; they were often rigged to be flashing and blinking, and utilized different color glass to vary the effect. Many of these signs were later retrofitted with neon.

Some metal signs created a similar effect with clever punch-outs that were backlit:

The early neon era dates to the late 1920s to the mid-1930s, with an example being this wreath sign—complete with a charming wintry home scene—by Claude Neon Russell of Rochester, New York. The following photos showcase some of the later neon signs in the museum’s collection.

I also was fortunate to see the signs before the neon lights were turned on, allowing me to revel in the brushwork, which was delightfully loose—after all, no one was ever going to be that close in “real life.”

A long stretch of the museum consists of Main Street, which blends past and present with storefronts painted by some of today’s best—like Noel Weber, Jeffrey P. Lang, and Lee Littlewood—that accompany the historical signs surrounding each fictional business. I inexplicably do not have any photos of the storefronts, but you can get a sense of it in this video of the neon turning on for the day:

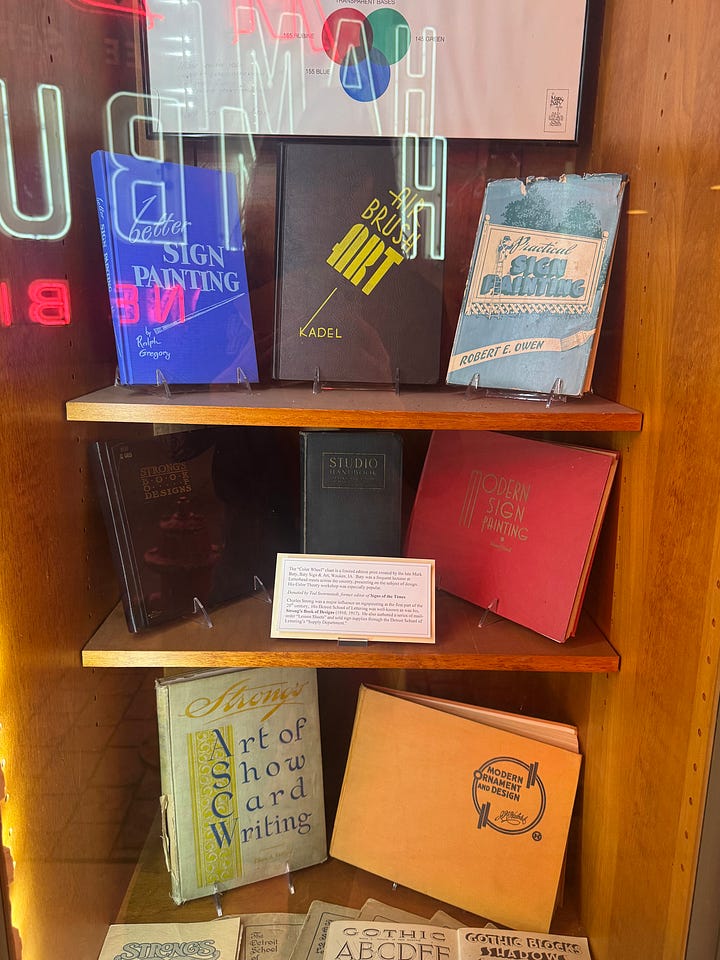

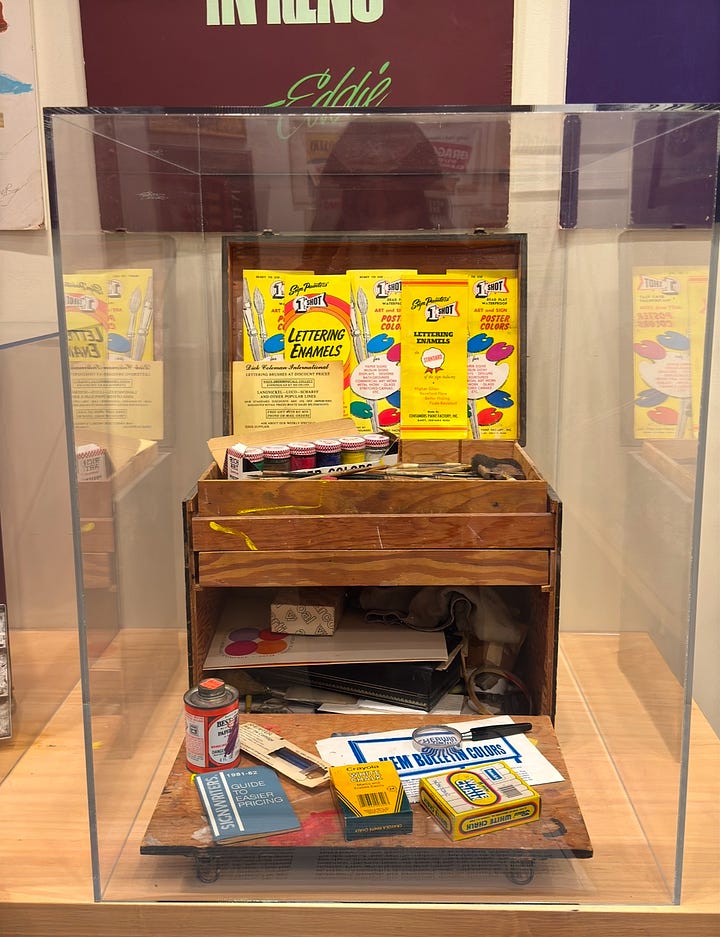

Peppered throughout the museum and within each storefront are glass displays filled with all kinds of sign painting goodies: toolkits from sign painters of the past, sign painting and trade books, and other examples of different sign types.

Early gilders would tote around their box of miniature glass samples to show off the different effects that were possible.

If you’re visiting and are serious about signs, I recommend booking a free appointment to spend time in the library, which is stocked with a collection of what feels like every sign-related book ever published, including first editions of treasured reference books like “Atkinson” Sign Painting and Henderson’s Sign Painter. It’s also home to the hardbound collection of Sign of the Times magazine from 1906 to 2020.

This museum is an absolute must-visit for anyone who either makes signs or love signs. I’ll be back in June for Letterheads 50—hope to see some of you there.

The Quench Tank

In keeping with the theme of The Anvil and the figurative blacksmith shop of my mind, the Quench Tank is my version of water cooler talk where I debrief on what’s happening lately in my world.

Per usual, I’ve been a little too busy lately. My email inbox is genuinely scary, there are sign projects that need to be done like yesterday, and I still have to do my freaking taxes (which feels so pointless given the state of our government, but here we are). Outside of the never-ending to-do list, I have been dealing intermittently with feelings of burnout and a general lack of excitement around sign painting. Thankfully, between attending Conclave (a gilding meet-up) in February and meeting up with Sam Roberts at the American Sign Museum, I am now absolutely buzzing.

Over a bowl of Cincinnati chili (a local delicacy of chili served on top of spaghetti and copious amounts of cheese, which I was skeptical about but actually really enjoyed), I was lamenting to Sam about these feelings of burnout.

Sam listened thoughtfully to my woes, and then proceeded to tell me that the Letterheads (an annual gathering started by a group of sign painters in the 1970s) actually started because of that feeling—of how making signs for businesses (or doing repetitive jobs as apprentices) and not tapping into the artform of signs left them feeling a lack of fulfillment. They decided to get together to teach themselves the long lost skills behind decorative sign making, like gilding or glue chipping or using smalts. Keep in mind, these are the very same sign painters I look up to, so knowing that they felt how I felt was exactly what I needed to hear.

All these new experiences (with a dash of sleep deprivation, which tends to leave me feeling very emotionally open) have felt like dunking my brain in a cold plunge and emerging with an overflow of gratitude, alignment, and ideas. I am still sifting through all the things I saw, and will be spending time brainstorming the new directions I’d like to take my art. The American Sign Museum isn’t just humming with neon, but with the spiritual charge of thousands of brush strokes by real people, real sign painters, who cared deeply about the object they were making, and the magic is palpable.

Beyond the dissolution of my creative block, I find myself in awe of how many lovely people there are in this world, and how there seems to be no limit to how many people I can connect with and call a friend. When you move with intention and passion and kindness, when you approach others with curiosity and care, the world opens itself up to you. The curiosities, synchronicities, and lessons of life are endless, and it is such a blessing to be bathed in this (neon) light.

Until next time,

Jenna

Thanks so much Jenna for this post! I hope to one day see the museum, and to go to a Letterheads, maybe when I’m more confident in my skills and work. The video of all the neon turning on - WOW! I appreciate you sharing your feelings of burnout, and glad to hear that you’re feeling positive again. Keep up the good work!

Very cool!!